Sea into the future

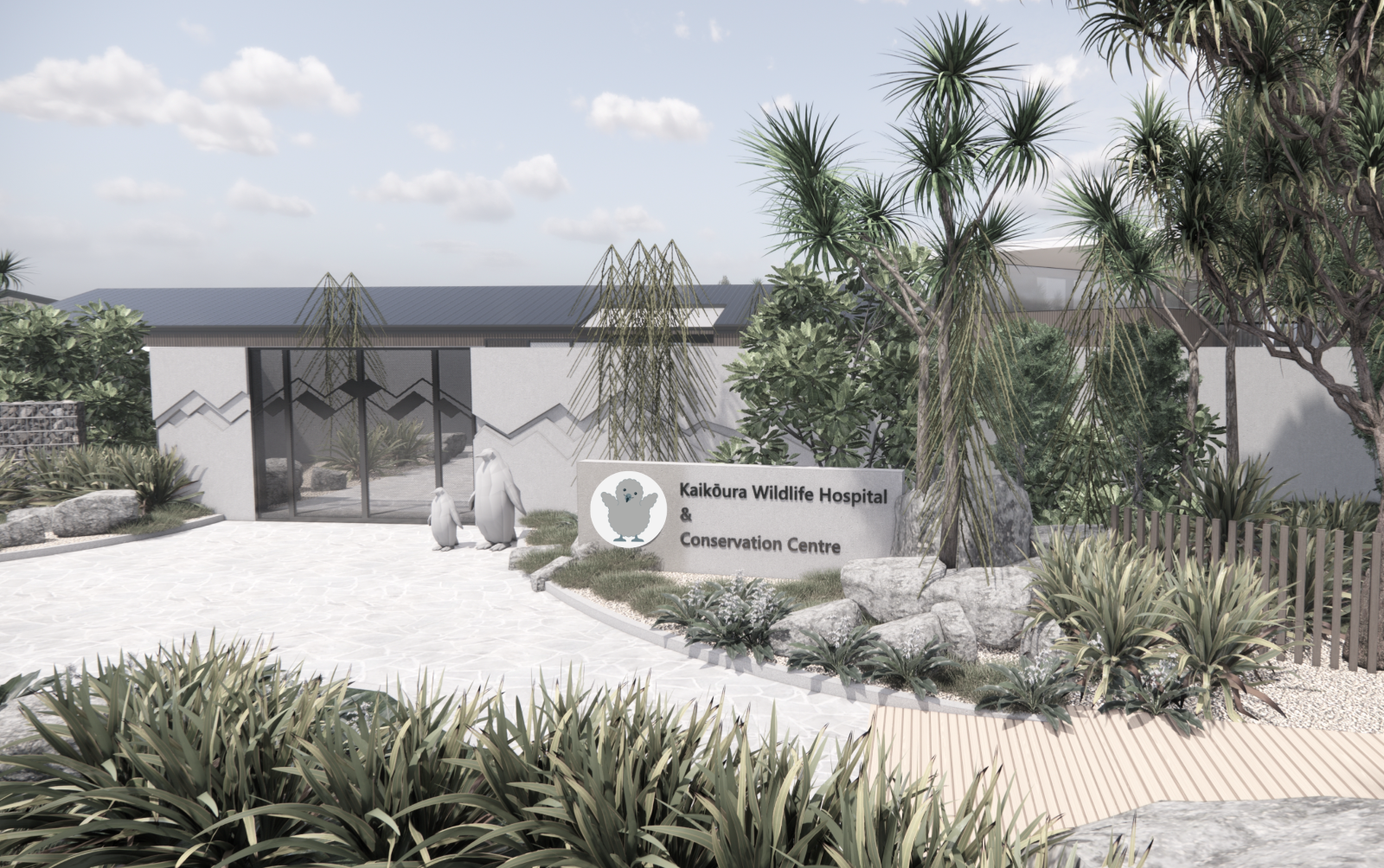

A concept of the proposed Kaikōura Wildlife Hospital and Conservation Centre, a future hub for rescue, rehabilitation, and education.

Kaikōura Wildlife Centre Trust founder and project manager Sabrina Luecht has just been feeding little penguin/kororā chicks, and like everything she is involved in, the wildlife biologist and rehabilitator has given more of herself than expected. She talks with Alistair Hughes.

“Caring for wildlife is a privilege but handling unwell birds is stressful,” Sabrina ruefully explains. “So with penguins, I’ve constantly got bites and bruises. I always say, ‘it's like feeding a ‘micro pitbull’!”

Sabrina is the only DOC-authorised wildlife rehabilitator in the Kaikōura region, and she established Kaikōura Wildlife Rescue in 2017, voluntarily dedicating herself to aiding injured, ill and endangered birds. And incredibly, she does it all on her own.

But as usual, she is quick to shift focus back to the larger problem. The aforementioned penguins happen to be a good entry point into outlining some of the challenges she faces in her voluntary role.

“Kororā are nocturnal, so you shouldn't be seeing them on land and in broad daylight – this indicates they are unwell. They're normally pretty secretive, and they don't want a bar of us. People generally care about and report unwell penguins, but not necessarily seabirds, which aren’t deemed ‘charismatic species’ like the red-billed gulls/tarapungā. They fall through the cracks because people have very little compassion for them. That is where education to raise awareness is critical, and that's half of what I spend my time doing.”

Red-billed gulls are not only a threatened species but are regarded as a ‘canary in the coalmine’ indicator of the overall health of the marine ecosystem. And those indications are anything but encouraging: Kaikōura is home to the largest remaining mainland red-billed gull colony, but the current rate of decline suggests that this may also vanish. Creating understanding of an imminent ecological crisis is one of Sabrina and the Trust’s greatest challenges, particularly as the natural environment of Kaikōura, on the surface at least, still appears to be a perfect Tourism New Zealand poster child.

Beyond its scenic beauty, the region owes much of its ecological richness to a rare geological feature found in few places around the world. “We have a deep water trench (the Kaikōura canyon) replicating a deep water ecosystem that you would normally find a long way offshore, but here it is close to the mainland,” explains Sabrina. “And that makes it really productive, because we’ve got this deep, cold, nutrient-rich water mixing with shallow coastal water.”

The rich biosystem which thrives in these special conditions has enabled Kaikōura’s famous wildlife diversity, an abundance of marine life normally only encountered many days from land, including two-thirds of the world’s albatrosses in these waters alone and the famous sperm whales. Consequently, ecotourism has thrived in the small, otherwise geographically isolated community. But as is often the case, this very factor is also threatening the continued survival of the wildlife which helps generate it.

When Sabrina relocated to Kaikōura eight years ago, she says mass species starvation due to decreased ocean productivity was just on the cusp of becoming a huge concern. Human-induced and climatic pressures on the environment have resulted in ocean food stocks no longer being as plentiful as they once were, catastrophically depleting the entire marine food web.

“It’s now escalating across the marine ecosystem in terms of overfishing and climate change, and decreased ocean productivity. That’s not unique to Kaikōura, it’s happening around the world. What is different here is the sheer species diversity. And all these species congregated in our waters are telling us the same thing, and the impacts on species loss are undeniable.”

Sabrina also points out that Kaikōura is a magnet for recreational fishing, exacerbating the problem to an extent not seen in other regions.

“Businesses rely on Kaikōura having a thriving marine ecosystem, and so they should care. There are thousands of seals and seabirds dying every year due to starvation. Currently there are only three resident sperm whales remaining, whereas in the 1990s, there were 87.” She notes that new sperm whales do occasionally visit, but pointedly do not remain, further indicating the deterioration of the once favourable environment.

“If we don't address this, we're going to lose a lot of species diversity. In a region such as this, social and environmental prosperity are closely interlinked. We need this ecosystem to function not just for wildlife, but for us.”

It could be regarded as a hopeless situation, but Sabrina is not the kind of person to give up.

“It's a really fine line when you're educating others, because you want to pivot it back to hope,” she says. “We’ve slowly seen attitude shifts, but I would argue it's generational. I'm not anti-fishing by any means. I try to look at things very pragmatically, with a sustainability focus. We should take only what we need, and try to be a bit more responsible. I can't live in a place like this and sit by and do nothing, I’m driven to try and enable positive change.”

Very aware that even with all the passion in the world an individual can’t change global issues on their own, Sabrina founded the Kaikōura Wildlife Centre Trust. As a registered charity all operational aspects of the Trust are reliant upon volunteer management, sponsors, donors and in-kind partnerships. Meanwhile, Sabrina continues to provide animal husbandry and medical skills, while progressing the vision to develop an urgently needed wildlife hospital.

“Kaikōura Wildlife Centre Trust is sort of a play on words, because we’re already an ‘international centre’ in terms of biodiversity but equally, we could create a wildlife hospital centre to ensure that wildlife can thrive here. Education is also critical; we need to mitigate human related threats, inspire young people, and showcase conservation in action.”

The brand Project WellBird was created to fulfil the first of two stages in eventually establishing a world class wildlife hospital and education complex in what is acknowledged as ‘New Zealand’s seabird capital’.

“We realised it could be 10 years until we achieve fundraising goals to facilitate construction of a multi-million dollar facility,” says Sabrina. “The birds, in the meantime, need some level of emergency care, and so achieving stage one involves acquiring five modular units, diagnostic equipment and wildlife vet services for isolation, triage, treatment, surgery, housing, rehab and recovery.”

The first portacom unit is housed on private land via an in-kind lease from Ben Foster Sculpture, until a permanent site and the rest of the units are secured. She is currently in discussion with the district council regarding finding an appropriate site, and is dedicating herself this year to applying for funding for stage 1.

She knows that it won’t be an easy task, but a close to $87,000 feasibility study funded by the Lottery Commission has shown it is a vision worth pursuing.

“When I talk about this project, it's really multi-generational. I view myself merely as a coordinator, setting in motion a long-term vision to bring people on board. We want young people who are passionate to carry the mantle in the long-term. I envision a biodiversity hub and community asset for our environment and I hope it goes on for many decades, long after I am gone.”

To support the Trust’s efforts visit projectwellbird.org